Inputs of the Future

Seeds of the Future

With fertiliser, agricultural chemicals and fuel covered in the first three editions, this final edition focuses on seed. This series is designed to serve many stakeholders including growers, government policy makers and industry.

The aim of this report is to examine the current state of Australia’s seed supply and breeding pipeline, followed by a more in-depth analysis of what the future of seed genetics and breeding could look like. These insights are intended to inform government policy making and regulation, as well as

being an informative guide for Australian grain growers.

From the report

How does plant breeding work

The plant breeding process is often referred to as a pipeline. At any time within a breeding program there can be thousands of different lines in development going through the process of being trialled, selected and cross bred to generate a suitable variety, at which point seed companies play a role in bulking up and distributing the seed to growers.

The use of biotechnology in plant breeding

Biotechnology refers to a suite of innovative technologies and a variety of applications that can be used in plant breeding. This includes the use of molecular markers to ensure target genetic traits have been successfully passed down through breeding, new breeding techniques and gene technology.

Tools to deal with future challenges

Genetically modified varieties provide Australian growers with a new generation of tools to deal with future challenges. In Australia, GM crops have been commercially grown since 1996 when Australian cotton farmers began the use of pest resistant varieties.

What are the current regulations for GM crops grown in Australia?

In Australia, the regulation of GM crops is overseen by several government agencies at the federal and state levels.

Crop genetics and technology

Australian grain growers are in a contest to obtain and deploy the very latest crop genetics and technology to remain globally competitive. Having access to the best crop genetics for our conditions and to meet market requirements allows grain growers to increase their resilience to a changing climate, increase profitability and contribute towards better environmental outcomes.

Fuels of the Future

Australian ag faces a significant challenge on the path to decarbonisation. Diesel is an essential input for grain growing and typically makes up approximately 85% of the energy used on farm.

GrainGrowers’ third edition of the Inputs of the Future series explores fuel alternatives and considers the impact and benefits on how growers operate. The report also looks at the costs and timelines of adoption in a grain context.

From the report

Green Hydrogen

In Australia, hydrogen vehicle technology is receiving investment from both federal and state governments. Creating hydrogen currently is an energy intensive process that uses the process of electrolysis. In this process electric current is applied to water to produce hydrogen and oxygen.

Battery Electric Vehicles

Unlike hybrid vehicles, which use a combination of an internal combustion engine and an electric motor, Battery Electric Vehicles rely solely on electric power for propulsion. They produce zero tailpipe emissions and like hydrogen, provide another emissions reduction solution if recharged by renewable sources

Bio and Renewable Fuels

Biofuels present an opportunity to reduce carbon equivalent emissions using existing machinery and infrastructure. For grain growers, this reduces immediate capital outlay for machinery upgrades (to new electric or hydrogen technologies under development and not available at scale to market) while participating in emission reduction benefits.

Fuel Agonistic Vehicles

The uncertainty of which technologies may win the race for powering farm machinery and transport means it is likely that there may be at least, in the near to mid-term, an increased share of fuel-agnostic vehicles that come into development and enter the Australian market. This is already occurring in a number of key sectors such as mining where heavy vehicles have a long service life.

Agriculture's transition to zero emissions vehicles

There are several factors currently inhibiting the transition from fossil fuels to renewable fuels in the grain freight supply chain, including technological availability and maturity, operational complexity, and asset investment life cycles.

Agriculture’s transition to zero emissions vehicles will require a coordinated, strategic and responsive approach with collaboration across the supply chain. For net zero fuel ambitions to be fully realised, policy makers must continue to consider ways to incentivise farmers to transition to low emission technology. It is equally important that government considers its ambitions and targets in the context of the technological availability of low and zero emissions farm and transport machinery being available in market at scale and at cost levels comparable to, or superior to, higher emissions technology platforms.

Chemicals of the Future

The targeted and responsible use of agricultural chemicals is vital to Australian grain farming, delivering food security, economic stability, and environmental sustainability.

The second edition of the Inputs of the Future series provides a holistic overview of chemical usage and where the products come from and covers Australia’s regulatory approach to agricultural chemicals, improved environmental impact and dependence on imported products.

Types of Ag Chemical

Herbicides

Herbicides, the largest class of agricultural chemicals used by volume in Australia. In the modern era, herbicides play a pivotal role in ensuring a continuous supply of nutrition for an ever-expanding global population.

Insecticides

Without insecticides, entire crops across vast geographic regions often face the imminent threat of devastation, or at the very least, significant degradation, rendering the remaining grains, pulses, or oilseeds unmarketable. The evolution of insecticides has undergone a remarkable journey over the years, culminating in the sophisticated formulations available to modern-day growers.

Fungicides

Fungicides are broadly classified into two categories: preventive fungicides, which ward off fungal infections in plants, and curative fungicides, which combat existing infections but are not particularly effective on most plant fungal infections. The development and the future of novel fungicides depends on and will be tailored to the specific pathogens affecting crops, both at home and abroad.

The extent of Australia's dependence on international supply chains for agricultural chemicals cannot be underestimated.

While Australia does engage in some imports and formulation of agricultural chemicals the domestic large-scale production of such chemicals is unlikely due to economic and resource constraints. Even in the event of a disruption to international supply chains, Australia would face significant challenges replacing imported agricultural chemicals vital for its food production.

Given this reliance on imported chemicals, the primary focus should be on effectively managing the complexities of the global supply chain. Australia stands out for its world-leading regulatory systems, commitment to stewardship, and science-based approach in registering, using, and overseeing agricultural chemicals.

Australian grain growers are recognised for their innovation and the adoption of best practices on a global scale. They readily embrace new technologies that reduce the overall use of agricultural chemicals, driven not only by environmental concerns but also economic imperatives to maintain competitiveness on the global stage.

Fertilisers of the Future

Strategic application of fertilisers is crucial to any farm business. In GrainGrowers’ 2023 Annual Policy Survey, Farm Inputs was identified as the biggest issue growers face, with 97% of challenges falling under this category. Fortunately, there are technologies and projects on the horizon, that with the required government policy and investment settings, may help alleviate the issue.

The first edition of the Inputs of the Future series takes a deep dive into each of the ‘’big three’’ fertiliser inputs - nitrogen (N), phosphorus (P) and potassium (K). It examines emerging technologies for each input, and looks at when these technologies could be available on farm. The full report covers the science behind fertilisers, usage statistics and some of the innovations on the horizon.

The 'Big Three' Fertilisers

Nitrogen

Australia has more recently become entirely reliant on the importation of urea. This is largely due to high and globally uncompetitive domestic operating cost structures for domestic producers, particularly for those that utilise natural gas in the production process of ammonia and urea manufacture. A large time lag exists between the mobilisation of new projects and technology to bridge the gap to locally produced urea. This means Australia is likely to remain wholly reliant on imports for some time to come without the government structurally lowering the input cost of natural gas.

Phosphorus

Only approximately a third of Australia’s nutrient phosphorus needs are serviced by domestic sources despite Australia’s abundant natural supply and processing capability of phosphate ore. This is due to the great distance between Australian phosphate mines and cropping regions. As a result, Australia imports most of its nutrient phosphorus rather than relying on a locally abundant supply. In the future, domestic supply is set to dramatically increase with the Ardmore Phosphate Rock Project initiated by Centrex.

Potassium

Until recently, Australia has been reliant on imported potassium-based fertilisers, however this is changing with the recent activation of sulphate of potash (SOP) production projects in Western Australia. These projects could allow Australia to be self-sufficient in the supply of high-quality potassium (K) fertiliser. This would meet both the objective of increased local manufacturing and employment while lowering the cost of K to farmers.

Worldwide fertiliser use by nutrient 1961-2020

The Right Settings

Australia has become increasingly reliant on the importation of fertiliser in recent years, particularly nitrogen-based fertilisers. Fortunately, there are technologies and projects on the horizon, that with the required government policy and investment settings, may turn the tide on this reliance.

What is needed

Government needs to make targeted co-investments whilst forging favourable policy settings promoting the establishment and retention of new domestic fertiliser operations.

Role of government

There are significant upfront costs in establishing new production capability for individual firms looking to introduce cleaner, lower cost fertiliser production initiatives. The additional hurdle for firms when considering entry into the market is scaling up production to the point where there are economies of scale in order to compete with incumbents.

As it is often difficult for startup firms to raise sufficient capital to enter the market and sustain production, there is a clear role for government in solving this market-based problem through targeted co-funding.

Government and policy makers should focus on the deployment of government funding mechanisms, such as the recently passed National Reconstruction Fund, to assist a transition to a lower cost, greener domestic fertiliser manufacturing base. Specifically, in relation to phosphorus and potassium-based fertiliser production initiatives, there is an opportunity for government engagement to co-fund these fledgling industries, with numerous shovel-ready projects on hand.

In relation to nitrogen-based fertiliser production, a much larger technological gap exists, inhibiting local investment in Australia. As such, the efforts of government should focus on funding initiatives that bring current timelines for new technological advancement forward.

Why it is needed

Australia needs greater reliability and timelessness of supply which will be underpinned by increased domestic production and will also have lower green house gas emissions. A substantive benefit of domestic fertiliser manufacturing is the considerable shortening of supply chain lead times meaning Australia is less beholden to the tyranny of distance. Currently, it takes an average of 8 to 10 weeks to import additional bulk fertiliser due to changes in demand (depending on the international origin).

Other major benefits through onshoring Australia’s fertiliser supply include local job creation, increases to domestic Gross Domestic Product (GDP) and the ability of government to have control over the manufacturing standards and emissions of these new operations.

Role of industry

The role of industry, including representative bodies and research organisations is to work cohesively and assist in guiding government initiatives and policy settings toward the highest optimal outcomes for local, low-cost manufacturing of fertiliser.

Australian fertiliser policy landscape

Australia’s economic and environmental policy settings are crucial if investment in new technology is to be embraced and proven to be commercially viable by private industry.

Domestic fertiliser producers are faced with very low barriers to entry from competing fertiliser imports, whilst simultaneously facing very high energy and labour costs relative to global standards. As fertiliser is a globally traded mass volume commodity where Australia is a price taker, large scale investment in domestic production is challenging in the absence of carefully implemented government support.

Government policy settings and investment initiatives should remain cognisant of fluctuation in commodity prices which, at extremes, can blur the long-term viability of certain technologies and initiatives.

The high cost of production may be sustainable at a business and consumer level for a short period of time due to supply shortages (such as during the COVID-19 pandemic) but under normal conditions the cost structure of new technologies must make the innovation economically viable (or provide a clear pathway to being economically viable).

New ventures must be able to weather multiple inevitable market cycles and the onslaught of global competitors for them to be a convincing value proposition for growers and investors alike.

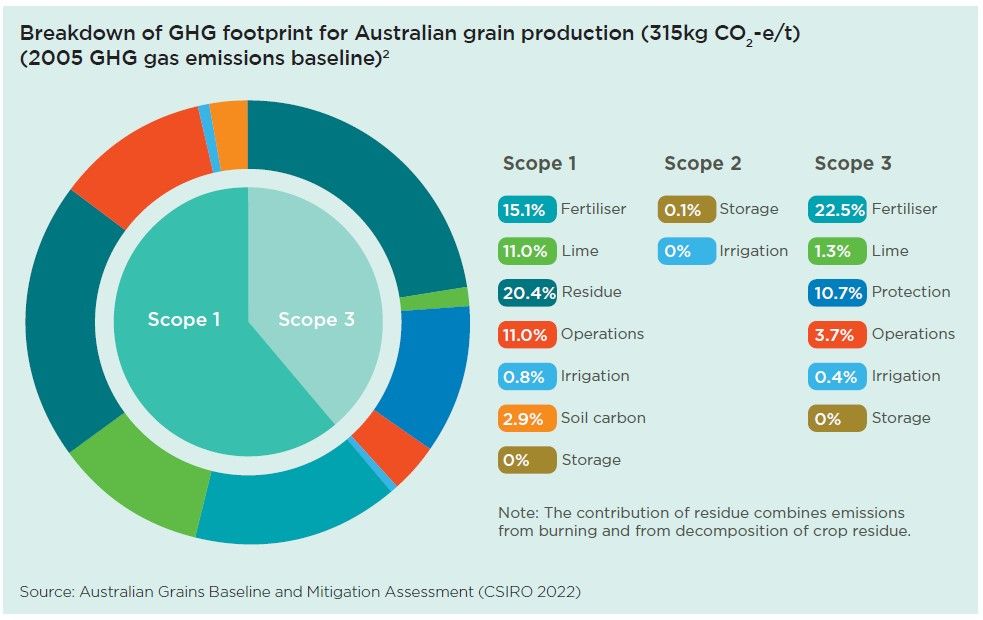

Embedded emissions in grain production

It should be noted that a substantial proportion (circa 25% 1) of grain growing greenhouse gas (GHG) emissions originate from beyond the farm gate. The majority of this comes with fertiliser and the associated transportation residing on the GHG bottom line as scope 3 emissions.

As shown below, Australian grain growers already apply very low rates of nitrogen per hectare by global standards and practice good stewardship by avoiding the over application of fertilisers. Hence aside from potentially using fertiliser inhibitor products, such as coated urea, further technological advancements, that are not necessarily available today, are required to improve the emissions efficiency of fertiliser use on farm.

Many of the technologies proposed in this report seek to lower farming Scope 3 emissions. In the instance of decentralised urea, bringing the production of urea back to a farm location level (or very close to), reduces the associated transportation emissions, (both road and ocean freight).

Where to from here?

Australian agriculture is dependent on the addition of fertiliser to crops and plant life to sustain the food security of our nation.

Having examined the ‘’big three’’ fertiliser inputs in depth, the challenges to government and industry through the transition to lower emission technologies are clear.

In order to foster domestic fertiliser production government policy settings need to strike a fine balance between being aspirational in terms of a transition to a lower emissions domestic capability, while remaining cognisant of large gaps (particularly with urea) in both availability and the production cost of new technologies.

As shown in the report, nitrogen-based fertiliser production poses the hardest challenge in terms of onshoring ahead of distant timelines set by industry, while phosphorous and potassium are areas where government incentives or investment could accelerate the domestic industry forward at speed.

Fertiliser is a globally traded commodity. Domestic producers face high-cost structures and are challenged by low barriers of entry from importers. Government policy must be reconciled against the backdrop of global competition, with Australia having some competitive advantage, particularly in the production of phosphorus and potassium-based fertiliser, thanks to an abundance of local raw materials.

Targeted investment or incentives for economically viable projects, of which some are shovel-ready, provide a starting point for government and the private industry to invest whilst aligning with the overarching objective of government to create a more robust and self-sufficient fertiliser manufacturing base with substantially shorter supply lead-times.

The full report covers the science behind fertilisers, usage statistics and emerging technology.

Farm Inputs

Farm inputs are critical to Australian grain production. Growers need surety of supply of farm inputs to maintain production including increased access to 'green' inputs. GrainGrowers aims to see growers have improved access to key farm inputs and more information to underpin decision-making.